Learning Objectives

- Identify the four eons of geologic time by the major events of life (or absence thereof) that define them, and list the eons in chronological order

- Identify the fossil, chemical, and genetic evidence for key events for evolution of the three domains of life (Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya)

- Describe the processes that caused the oxygenation of the atmosphere and the evidence for it

- Describe the hypotheses explaining the causes and results of the Cambrian explosion

- Place and identify the three domains of life on a phylogenetic tree

- Use cellular traits to differentiate between Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya

- Define photo-, chemo-, auto-, and hetero-trophy, and identify which domains of life can accomplish each metabolic strategy

- Describe the importance of prokaryotes (Bacteria and Archaea) with respect to human health and environmental processes

Geologic Time and the Evolution of Life on Earth

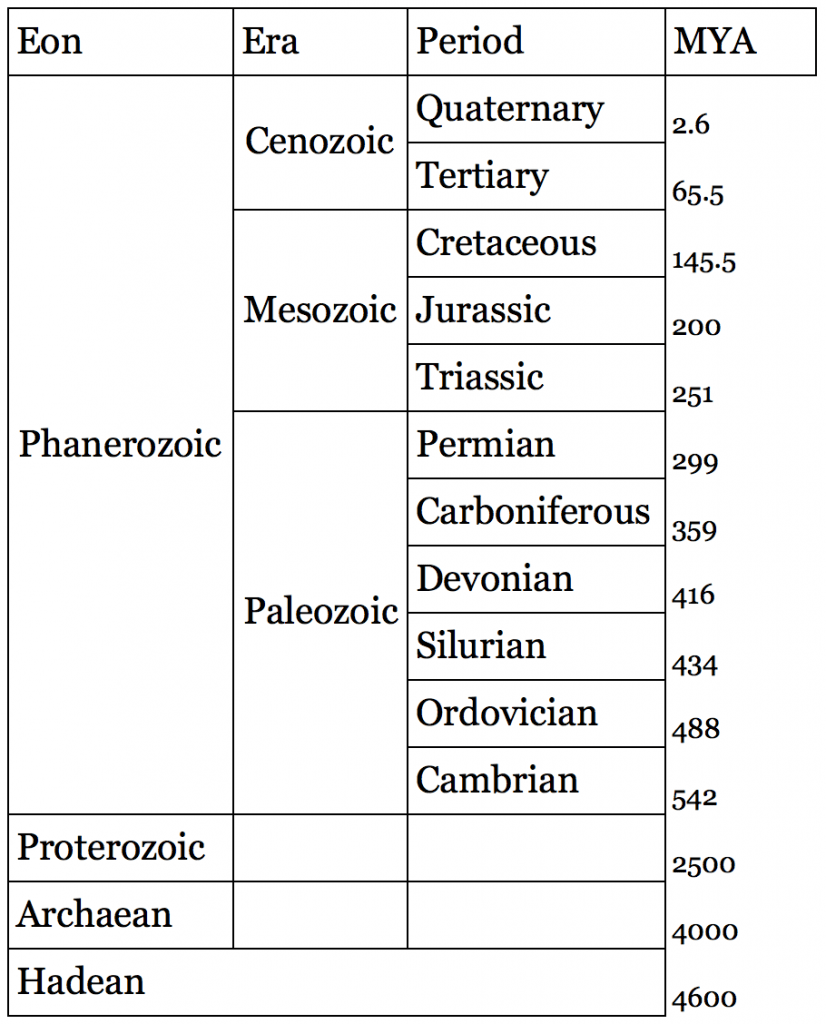

The story of the history of life is one of diversification, which is the proliferation of new taxa, and extinction, or the loss of taxa: 99% of all species that ever lived are now extinct. Evidence for life in the past is embedded in the rock record as fossils and trace fossils, like oil or coal beds in the place where and when many organisms died. The earth is 4.6 billion years (BY) old, so geologists work on immensely long time scales broken into four eons of geologic time, defined by how many billion years ago (BYA) or million years ago (MYA) they occurred:

- Hadean (4.6-4.0 BYA): occurred before life arose (or at least, before there is compelling evidence of life)

- Archaean (4.0-2.5 BYA): featured the evolution of early life, including bacteria, archaea, and the first cyanobacteria capable of oxygenic photosynthesis

- Proterozoic (2.5 BYA-542 MYA): featured oxygen accumulation (the Oxygen Revolution), and the first single-celled and multicellular eukaryotes, and the flourishing of early microbial and multicellular life

- Phanerozoic (542 MYA to present): beginning with the Cambrian explosion, features the proliferation of animal and plant life

The eons we will focus on are subdivided into a series of eras and periods. Famous eras you may already have heard of include the Paleozoic, which literally translates as “old life.” The well-known periods may also familiar: the Cambrian is when animal life diversified greatly, the Carboniferous featured land plants, the Jurassic and the Cretaceous are remembered for domination and demise of the dinosaurs. We will take time to place organism groups into their eons, eras, and (rarely) periods, so it’s worth orienting yourself to the geologic time scale before we begin to meet the diversity of life that lived in the past and were the ancestors to modern taxa.

Evolution of Three Domains of Life on Earth

The information below was adapted from Wikipedia “Earliest known life forms” and OpenStax Biology 22.2

DNA sequence comparisons and structural and biochemical comparisons consistently categorize all living organisms into 3 primary domains: Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya (also called Eukaryotes; these terms can be used interchangeably). All three domains of life share a single common ancestor. Both Bacteria and Archaea are prokaryotes, single-celled microorganisms with no nuclei, and Eukarya includes us humans and all other animals, plants, fungi, and single-celled protists; all Eukarya are organisms whose cells have nuclei to enclose their DNA apart from the rest of the cell. The fossil record indicates that the first living organisms were prokaryotes (Bacteria and Archaea), and eukaryotes arose a billion years later.

The Earth is approximately 4.6 billion years old based on radiometric dating. While it is formally possible that life arose during the Hadean eon, conditions may not have been stable enough on the planet to sustain life because large numbers of asteroids were thought to have collided with the planet during the end of the Hadean and beginning of the Archean eons.

Earliest life on Earth: Physical and chemical evidence suggest life arose on Earth during the Archean eon: The earliest undisputed evidence for life on Earth includes microfossils (literally “microscopic fossils”) suggests that life arose on Earth between 3.5 and 3.8 BYA, placing the origin of life in the Archean eon. The earliest biosignature evidence, or “chemical fossils,” chemical evidence of life, suggests early life may have been present as early as 4.1 BYA. Biosignatures include chemical isotopes or molecules that suggest biological activity, such as specific carbon isotopes and components of fatty acids, nucleic acids, and proteins. What were these early life forms like? For the first billion years of Earth’s existence, the atmosphere was anoxic, meaning that there was no molecular oxygen (O2). Thus, the first living things were single-celled, prokaryotic anaerobes (living without oxygen) and likely chemotrophic.

Additional evidence for early life on Earth includes fossilized stromatolites, which are laminated (layered) sedimentary structures produced by microbes as they create a sequence of multi-layered sheets composed of successive generations of microorganisms; each new generation grows on top of the previous generation, creating a layer of sediment below the living layer. The earliest known stromatolites date to 3.48 to 3.7 BYA, and are thought to have included photosynthetic bacteria (though not oxygenic photosynthesis – yet!)

The Oxygen Revolution: The evolution of oxygenic photosynthesis in early cyanobacteria initiated what is known as “The Oxygen Revolution,” (also “the Great Oxidation Event” and the “Oxygen Catastrophe”), which began about 2.6 billion years ago near the end of the Archean eon. In oxygenic photosynthesis, cyanobacteria split water to produce oxygen as a (toxic) byproduct, generating the first free molecular oxygen in early Earth’s atmosphere. The free oxygen produced by cyanobacteria immediately reacted with soluble iron in the oceans, causing iron oxide (rust) to precipitate out of the oceans. Oxygen didn’t accumulate all at once, and evidence indicates that the oceans weren’t fully oxygenated until 850 million years ago (MYA) near the end of the Proterozoic eon. Today we see evidence of the slow accumulation of oxygen in the atmosphere through banded iron formations present in sedimentary rocks from that period.

Banded iron formation, Karijini National Park, Western Australia. By Graeme Churchard from Bristol, UK – Dales GorgeUploaded by PDTillman, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=30889569

Origin of eukaryotes: Microfossil evidence suggests that eukaryotes arose sometime between 1.6 and 2.2 billion years ago during the Proterozoic, after the start of the Oxygen Revolution. Eukaryotes.

First multicellular life: Much of the life on Earth was singled celled until near the end of the Proterozoic eon. Multicellular life appeared in the fossil record approximately 600 MYA near the end of the Proterozoic. Evidence of this early multicellular life includes bizarre-looking fossils such as the Ediacaran biota and Doushantuo fossils that exhibit body plans unlike anything seen present-day animals.

The Cambrian explosion: The start of the Phanerozoic eon begins with the Cambrian explosion (also called the Cambrian radiation), an adaptive radiation that includes the emergence of nearly all modern animal phyla approximately 542 MYA. The appearance of Cambrian fauna span millions of years; they did not all appear simultaneously as the term “explosion” inaccurately implies; however, millions of years is very rapid in the context of geologic time.

The leading hypothesis to explain the Cambrian explosion is the accumulation of oxygen in the atmosphere from the activity of cyanobacteria (the Oxygen Revolution). The availability of oxygen facilitated the evolution of larger bodies and organs and tissues, such as brains, with high metabolic rates; it also resulted in mass extinction of many obligate anaerobic organisms (organisms that cannot survive in the presence of oxygen). The increase in oxygen is a dramatic example of how life can alter the planet. Evolution of oxygenic photosynthesis changed the planet’s atmosphere over billions of years, and in turn caused radical shifts in the biosphere: from an anoxic environment populated by anaerobic, single-celled prokaryotes, to eukaryotes living in a micro-aerophilic (low-oxygen) environment, to multicellular-organisms in an oxygen-rich environment. The video below provides an overview of the Oxygen Revolution (aka, the Oxygen Catastrophe), including its detrimental effects on the organisms that lived at the time:

Phylogenetic Relationships Between Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukarya

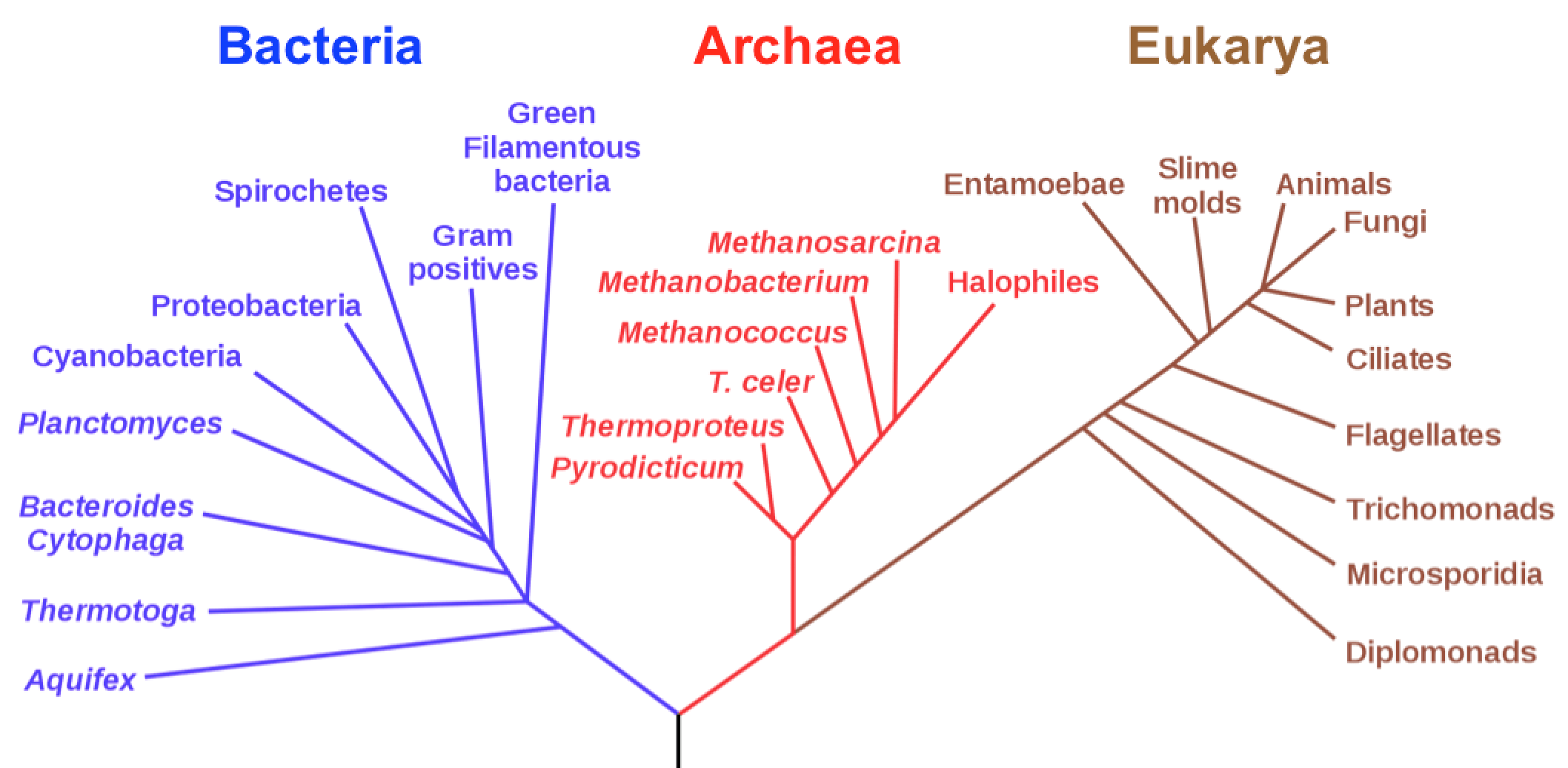

While the term prokaryote (“before-nucleus”) is widely used to describe both Archaea and Bacteria, you can see from the phylogenetic Tree of Life below that the term “prokaryote” does not describe a monophyletic group (i.e., it is impossible to draw a circle around bacteria, archaea, and their common ancestor without leaving out one of the decedents of the common ancestor):

In fact, Archaea and Eukarya form a monophyletic group, not Archaea and Bacteria. These relationships indicate that archaea are more closely related to eukaryotes than to bacteria, even though superficially archaea appear to be much more similar to bacteria than eukaryotes.

Similarities and Difference Among the Three Domains of Life

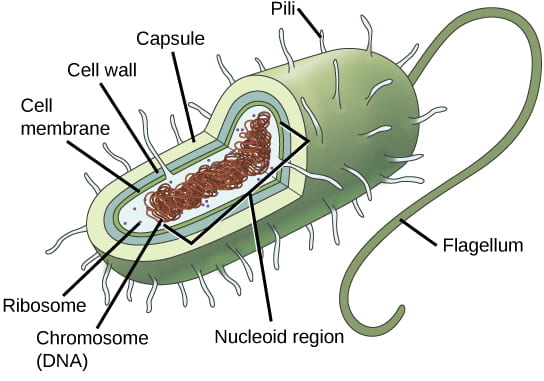

Eukaryotes are visibly different from Archaea and Bacteria, which share a number of features with each other; however, all three are distinct domains of life:

- Both Archaea and Bacteria are unicellular organisms; eukaryotes include both unicellular and multicellular organisms.

- Archaea and bacterial cells lack organelles or other internal membrane-bound structures; eukaryotes have a nucleus separating their genetic material from the rest of the cell as well as membrane-bound organelles

- Archaea and Bacteria generally have a single circular chromosome: a piece of circular, double-stranded DNA located in an area of the cell called the nucleoid; many eukaryotes have multiple, linear chromosomes wrapped around proteins called histones. (Note that DNA genomes are always composed of double-stranded DNA molecules, whether they are circular or linear chromosomes.)

- Archaea and Bacteria reproduce asexually through binary fission, a process where an individual cell reproduces its single chromosome and splits in two; eukaryotes reproduce asexually through mitosis, which includes additional steps for replicating and correctly dividing multiple chromosomes between two daughter cells. Many eukaryotes also reproduce sexually, where a process called meiosis reduces the number of chromosomes by half to produce haploid cells (typically called sperm or eggs), and then two haploid cells fuse to create a new organism. Archaea and bacteria cannot reproduce sexually.

- Archaea and Bacteria can share genomic information between individual cells which result in a phenomenon called horizontal gene transfer, also called lateral gene transfer. (Horizontal gene transfer is in contrast to vertical gene transfer, which is where offspring inherit genetic information from a parent as a result of reproduction). Horizontal gene transfer occurs when a cell acquires DNA from an external source, and it results in shared DNA between individuals that may not be genetically related. Horizontal gene transfer is the primary way that antibiotic resistance spreads through microbial populations.

- Almost all prokaryotes have a cell wall, a protective structure that allows them to survive in extreme conditions, which is located outside of their plasma membrane; some eukaryotes do have cell walls, while others do not. The composition of the cell wall differs significantly between the three domains of life:

- Bacterial cell walls are composed of peptidoglycan, a complex of protein and sugars.

- Archaeal cell walls are composed of polysaccharides (sugars).

- Eukaryotic cell walls found in plants are composed of cellulose, and the cell walls of fungi are composed of chitin.

The features of a typical prokaryotic cell are shown. Image credit: OpenStax Biology 22.2

Horizontal Gene Transfer and Prokaryotic Phylogenies

As previously discussed, genetic information is a commonly used data source to identify evolutionary relationships in phylogenetic trees. However, the prevalence of horizontal gene transfer among prokaryotes presents a challenge to using exclusively genetic approaches to resolving phylogenetic relationships among Bacteria and Archaea, because the presence of a particular gene in two different microbial species may not indicate homology but instead an instance of horizontal gene transfer. This is not to say that phylogenetic classification of prokaryotes is impossible (for example, phylogenetic analyses take advantage of genes that are less likely to be exchanged via HGT such as ribosomal gene sequences), just that some of the tools that work readily for most groups of eukaryotes do not work as well for most groups of prokaryotes.

Metabolic Diversity of Prokaryotes

The information below was adapted from OpenStax Biology 22.3

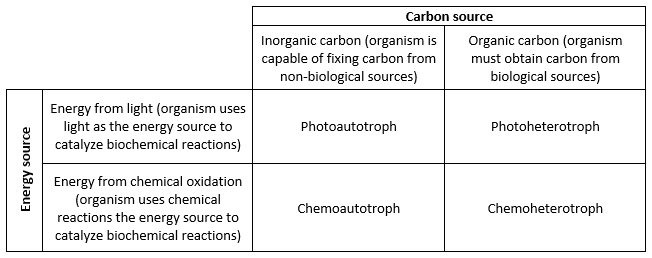

Because phylogenetic relationships among prokaryotes can be challenging to resolve to great details, prokaryotes are instead often classified based on metabolic and other traits. Prokaryotes have been and are able to live in every environment by using whatever energy and carbon sources are available. Prokaryotes fill many niches on Earth, including being involved in nutrient cycles such as nitrogen and carbon cycles, decomposing dead organisms, and thriving inside living organisms, including humans. This incredibly broad range of environments that prokaryotes occupy is possible because there is incredible metabolic diversity represented among different prokaryotic species. We can classify organisms by how they obtain their energy, and how they obtain their carbon:

- Classification by source of energy:

- Phototrophs (phototrophic organisms) obtain their energy from sunlight.

- Chemotrophs (chemosynthetic organisms) obtain their energy from chemical compounds.

- Classification by source of carbon:

- Autotrophs (autotrophic organisms) are able to fix (reduce) inorganic carbon such as carbon dioxide

- Heterotrophs (heterotrophic organisms) must obtain carbon from an organic compound

These terms can be combined to classify organisms by both energy and carbon source:

- Photoautotrophs obtain energy from sunlight and carbon from carbon dioxide

- Chemoheterotrophs obtain energy and carbon from an organic chemical source

- Chemoautotrophs obtain energy from inorganic compounds, and they build their complex molecules from carbon dioxide.

- Photoheterotrophs use light as an energy source, but require an organic carbon source; they cannot reduce (fix) carbon dioxide into organic carbon.

In contrast to the great metabolic diversity of prokaryotes, eukaryotes are only photoautotrophs (plants and some protists) or chemoheterotrophs (animals, fungi, and some protists). The table below summarizes carbon and energy sources in prokaryotes.

The videos below provide more detailed overviews of Bacteria and Archaea, including general features and metabolic diversity (please note, you can disregard the discussion on lithotrophs and organotrophs for the purposes of this course; in this course, we are using the term chemotroph to refer to all organisms that obtain energy from chemical oxidation, irrespective of whether they use organic or inorganic compounds):

The Importance of Prokaryotes to Human Health and Environmental Processes

The information below was adapted from OpenStax Biology 22.4 and OpenStax Biology 22.5

Some prokaryotic species can harm human health as pathogens: Devastating pathogen-borne diseases and plagues, both viral and bacterial in nature, have affected humans since the beginning of human history. In the 21st century, infectious diseases remain among the leading causes of death worldwide, despite advances made in medical research and treatments in recent decades. Of particular concern today is the increasing prevalence of antimicrobial resistance, facilitated by misuse of antibiotics and the capacity of many prokaryotes to readily share genetic information resulting in horizontal gene transfer.

But pathogenic prokaryotes represent only a very small percentage of the diversity of the microbial world. In fact, our life would not be possible without prokaryotes, and some prokaryotic species are directly beneficial to human health:

- The bacteria that inhabit our skin and gastrointestinal tract do a host of good things for us: They protect us from pathogens, help us digest our food, and produce some of our vitamins and other nutrients. They may even help regulate our moods, influence our activity levels, and even help control weight by affecting our food choices and absorption patterns. The Human Microbiome Project has begun the process of cataloging our normal bacteria (and archaea) so we can better understand these functions. In addition, the absence of certain key microbes from our intestinal tract may set us up for a variety of problems, particularly regarding the appropriate functioning of the immune system. There are intriguing findings that suggest that the absence of these microbes is an important contributor to the development of allergies and some autoimmune disorders. Research is currently underway to test whether adding certain microbes to our internal ecosystem may help in the treatment of these problems as well as in treating some forms of autism.

- A particularly fascinating example of our normal flora relates to our digestive systems. People who take high doses of antibiotics tend to lose many of their normal gut bacteria, allowing a naturally antibiotic-resistant species called Clostridium difficile to overgrow and cause severe gastric problems, especially chronic diarrhea. Obviously, trying to treat this problem with antibiotics only makes it worse. However, it has been successfully treated by giving the patients fecal transplants (so-called “poop pills”) from healthy donors to reestablish the normal intestinal microbial community. Clinical trials are underway to ensure the safety and effectiveness of this technique.

Carbon cycle; Image modified from “Nitrogen cycle” by Johann Dréo (CC BY-SA 3.0). The modified image is licensed under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license._

Other prokaryotes indirectly, but dramatically, impact human health through their roles in environmental processes:

- Prokaryotes play a critical role in biogeochemical cycling of nitrogen, carbon, phosphorus, and other nutrients. The role of prokaryotes in the nitrogen cycle is especially critical to other living things. Nitrogen is part of nucleotides and amino acids that are the building blocks of nucleic acids and proteins, respectively. Nitrogen is usually the most limiting element in terrestrial ecosystems, with atmospheric nitrogen, N2, providing the largest pool of available nitrogen. However, eukaryotes cannot use atmospheric, gaseous nitrogen to synthesize macromolecules. Fortunately, nitrogen can be “fixed,” (reduced) meaning it is converted into ammonia (NH3) either biologically or abiotically. Abiotic nitrogen fixation occurs as a result of lightning or by industrial processes. Biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) is exclusively carried out by prokaryotes: soil bacteria, cyanobacteria, and Frankia spp. (filamentous bacteria interacting with actinorhizal plants such as alder, bayberry, and sweet fern). After photosynthesis, BNF is the second most important biological process on Earth.

- Prokaryotes are also essential in microbial bioremediation, the use of prokaryotes (or microbial metabolism) to remove pollutants, such as agricultural chemicals (pesticides, fertilizers) that leach from soil into groundwater and the subsurface, and certain toxic metals and oxides, such as selenium and arsenic compounds. One of the most useful and interesting examples of the use of prokaryotes for bioremediation purposes is the cleanup of oil spills, including the Exxon Valdez spill in Alaska (1989), and more recently, the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico (2010). To clean up these spills, additional inorganic nutrients that help bacteria to grow are added to the area, and the growth of bacteria breaks down the excess hydrocarbons.

a) Cleaning up oil after the Valdez spill in Alaska, workers hosed oil from beaches and then used a floating boom to corral the oil, which was finally skimmed from the water surface. Some species of bacteria are able to solubilize and degrade the oil. (b) One of the most catastrophic consequences of oil spills is the damage to fauna. (credit a: modification of work by NOAA; credit b: modification of work by GOLUBENKOV, NGO: Saving Taman; from https://cnx.org/resources/b3178fe3228bf3c1f1ce0feae58ed67d7d1dad07/Figure_22_05_03ab.jpg)