Learning Objectives

- Distinguish between the functions of classes of sensory receptors (mechanoreceptors, chemoreceptors, photoreceptors, nociceptors, thermoreceptors), and identify example animal sensory systems that reply on each type of sensory receptor

- Explain the three general mechanisms by which the magnitude or degree of the stimulus (analog data) is accurately communicated via action potentials (digital signals) to the CNS

- Use mechanoreceptors and photoreceptors as model receptor types to describe examples of sensory reception in different animal lineages (eg visual systems, auditory systems, and vestibular sensory systems)

Sensory Receptors Allow for Sensory Perception in Animals

The information below was adapted from OpenStax Biology 36.0 and OpenStax Biology 36.1

The sensory system detects signals from the outside environment and communicates it to the body via the nervous system. The sensory system relies on specialized sensory receptor cells that transduce external stimuli into changes in membrane potentials. If the changes in membrane potential are sufficient to induce an action potential, then these action potentials are communicated along neurons within the afferent division of the PNS to the CNS for information processing. The CNS integrates and interprets the incoming signals to effect a response to the appropriate body systems via the efferent division of the PNS.

Sensory receptor cells can be either:

- specialized neurons (the receptor cell is also a neuron)

- specialized sensory cells which synapse with a neuron (the receptor cell secretes neurotransmitters to stimulate changes in membrane potential in the synapsed neuron)

Sensory receptor cells transduce (convert into changes in membrane potential) incoming signals and may either depolarize or hyperpolarize in response to the stimulus, depending on the sensory system. In vertebrates, each sensory system transmits signals to a different specialized portion of the brain such as the olfactory bulb (smell) or occipital lobe (sight), where the signal is integrated and interpreted to effect some sort of response (often motor output) via the PNS.

Different sensory receptor cells are specialized for different types of stimuli, and are categorized by the type of stimulus they detect. Sensory receptor cells include (but are not limited to)

- Mechanoreceptors: respond to physical deformation of the cell membrane from mechanical energy or pressure; mechanoreceptors detect touch (somatosensation), sound (auditory sensation), and balance (vestibular sensation), among many other sensory systems.

- Photoreceptors: respond to radiant energy (visible light in most vertebrates; visible as well as UV light in many insects); photoreceptors are present in all types of animal eyes, ranging from cup eyes to compound eyes to camera eyes

- Chemoreceptors: respond to specific molecules, often dissolved in a specific medium (such as saliva or mucus), or airborne molecules; chemoreceptors allow animals to taste and smell; chemoreceptors are likely the oldest of all sensory receptors and chemosensation evolved long before animals did; some form of chemoreception and chemosensory system has been identified in all living things so far

- Nociceptors: respond to “noxious” stimuli, or essentially anything that causes tissue damage; nociceptors detect tissue damage, not detect pain – our brain interprets perceived tissue damage as painful

- Thermoreceptors: respond to heat or cold

The function of any species’ sensory system has been driven by natural selection, and sensory systems differ among species according to their history of natural selection. For example, the shark, unlike most fish predators, is electrosensitive: it is sensitive to electrical fields produced by other animals in its environment.

Humans and many other vertebrates have at least five special senses (senses which have a specialized organ devoted to them): olfaction (smell), gustation (taste), equilibrium/vestibular (balance and body position), vision, and hearing. Additionally, we possess general senses, also called somatosensation, which respond to stimuli like temperature, pain, pressure/touch, and vibration.

Each sensory system, whether special or general, requires sensory receptors to detect the stimulus. In many cases, very different sensory systems can rely on the same type of sensory receptor; for example, both hearing and touch utilize mechanoreceptors.

Analog to Digital: Encoding and Transmission of Sensory Information

Sensory stimuli vary in intensity. For example, a sound can be a whisper or a shout. Yet the stimulus is transmitted via action potentials in the sensory neurons, which are “all or nothing” events that do not vary in intensity. How do we detect and perceive the difference between a shout and a whisper? The intensity or degree of a stimulus is often encoded in three different ways:

- The rate or frequency of action potentials produced by the sensory receptor. For example, an intense stimulus will produce a more rapid series of action potentials, and reducing the stimulus will likewise slow the rate of production of action potentials. (Note the intensity affects the rate of production of action potentials, not the speed with which the action potential travels along the axon or the action potential amplitude.)

- The number of receptors activated. For example, an intense stimulus might initiate action potentials in a large number of adjacent receptors, while a less intense stimulus might stimulate fewer receptors.

- Which specific receptors are activated. For example, a low pitch or will initiate action potentials in one set of sensory neurons, while a high pitch will initiate action potentials in a different set of sensory neurons.

Mechanoreceptors: Touch, Sound, Balance

Mechanoreceptors sense stimuli due to physical deformation of their plasma membranes. They contain mechanically gated ion channels whose gates open or close in response to pressure, touch, stretching, and sound. Mechanoreceptors are used for sensory systems that detect changes in pressure, ranging from pressure due to touch from a physical object to pressure caused by sound waves.

Mechanoreceptors and the Vertebrate Somatosensory System

The information below was adapted from OpenStax Biology 36.1

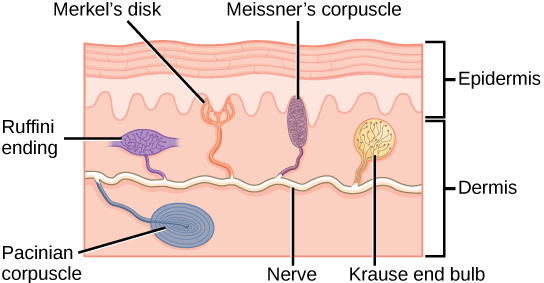

Somatosensation is the sense of touch. Somatosensation occurs all over the exterior of the body and at some interior locations as well. The sense of touch is detected by a variety of different types of mechanoreceptors that are embedded in the skin, mucous membranes, muscles, joints, internal organs, and cardiovascular system. In fact, what is commonly referred to as “touch” involves more than one kind of pressure stimulus and more than one kind of mechanoreceptor. Touch in humans includes four primary tactile mechanoreceptors in the skin. You don’t need to know the specific name for each type of touch mechanoreceptor receptor (shown below), but you should be able to recognize that

- some types of mechanoreceptors are located near the upper layers of the skin, and are thus more sensitive to lighter touch and are able to precisely localize gentle touch

- other types of mechanoreceptors are located deeper in the skin, and are thus only activated by stronger pressure and are not as highly sensitive to identify the precise location of the touch.

A light touch activates only the mechanoreceptors near the upper layer of the skin, while a firmer touch activates mechanoreceptors deeper in the skin, in addition to the mechanoreceptors near the surface of the skin. A firmer touch will also activate a greater number of receptors, and may induce more frequent action potentials in the receptors than a lighter touch.,

Mechanoreceptors and the Mammalian Auditory System

The information below was adapted from OpenStax Biology 36.4

Auditory stimuli are sound waves, which are mechanical pressure waves that move through a medium, such as air or water. (There are no sound waves in a vacuum since there are no air molecules to move in waves.) Because sound waves exert pressure, sound is detected by mechanoreceptors.

There are several important characteristics of sound waves that are important for understanding how hearing works:

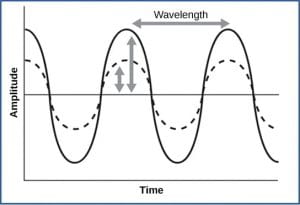

- Frequency is the number of waves per unit of time, which is heard as pitch. Frequency is also related to wavelength, where high-frequency (15,000 Hz) sounds are higher-pitched and shorter wavelength than low-frequency, long wavelength (100 Hz) sounds. Most humans can perceive sounds with frequencies between 30 and 20,000 Hz. Dogs detect up to about 40,000 Hz; cats, 60,000 Hz; bats, 100,000 Hz; and dolphins 150,000 Hz, and some fish can hear 180,000 Hz.

- Amplitude, or the dimension of a wave from peak to trough, in sound is heard as volume. The sound waves of louder sounds have greater amplitude than those of softer sounds. For sound, volume is measured in decibels (dB). In the figure below, the softest sound that a human can hear is the zero point. Humans speak normally at 60 decibels.

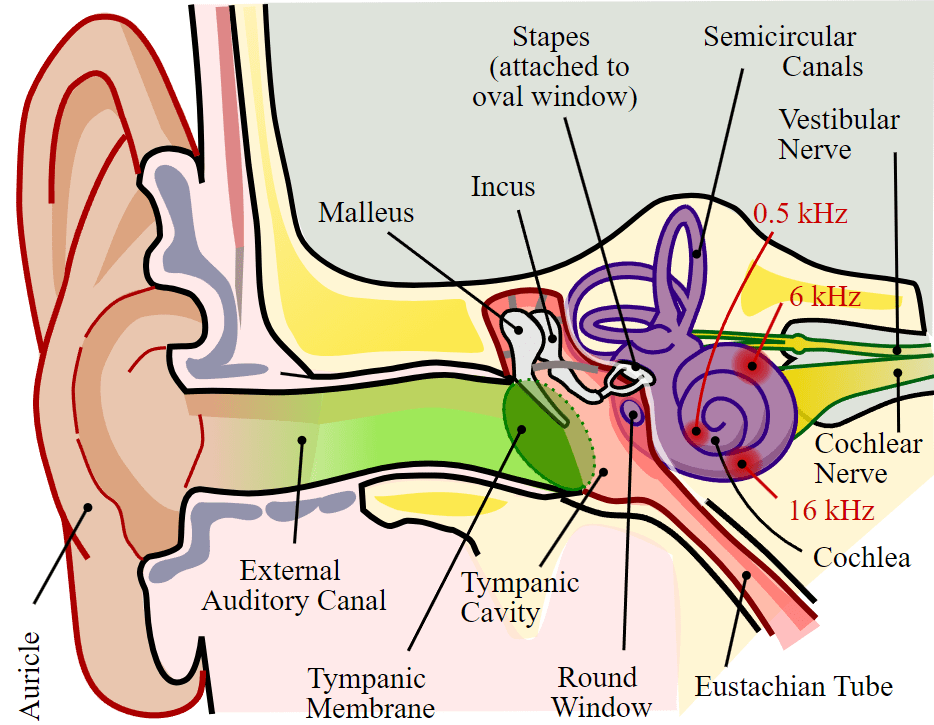

The outer ear collects sound waves, which travel through the auditory canal and cause the ear drum to vibrate; these vibrations transmit the sound to the middle ear, where three small bones called ossicles, which are unique to the mammalian ear, amplify the vibrations and transmit them to the inner ear; within the inner ear, the vibrations create pressure waves inside the fluid-filled cochlea, a “whorled” structure like the shell of a snail, which contains the auditory mechanoreceptors that allow us to perceive pressure waves in the air as sound.

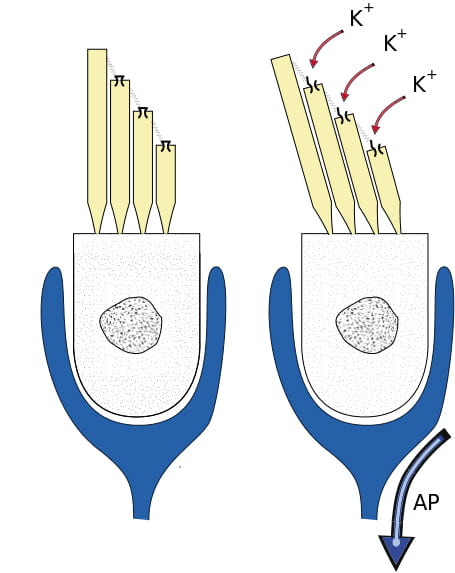

Located within the cochlea, the basilar membrane is a flexible membrane that runs the length of the cochlea and contains the mechanoreceptors called hair cells which transduce sound waves into action potentials. Hair cells have tiny hair-like protrusions on their surface called stereocilia; these hair-like features are the reason they are called “hair” cells. When the sound waves in the cochlear fluid contact the basilar membrane, the basilar vibrates in response, pressing the hair cells’ stereocilia against the tectorial membrane. When the hair cells is pressed against the tectorial membrane, it physically bends the stereocilia, initiating action potentials in the afferent neurons that communicate sounds stimuli to the brain.

We perceive sound volume based on how many hair cells are activated, and we perceive sound pitch based on which hair cells are activated. Different hair cells are activated by different pitches of sound because the basilar membrane’s flexibility changes along its length; it is thicker, stiffer, and narrower at one end of the cochlea, and thinner, floppier, and broader at the other end. As a result, different regions of the basilar membrane vibrate according to the frequency (pitch) of the sound wave conducted through the fluid in the cochlea, with the stiffer region vibrating in response to high frequency (higher-pitched) sounds, and the more flexible region vibrating in response to low frequency (lower-pitched) sounds. In other worlds, pitch is detected based on which region of the basilar membrane vibrates in response to a sound (and thus which hair cells are activated).

This video provides a quick overview of mammalian cochlear function in hearing:

Mechanoreceptors and the Vertebrate Vestibular System

The information below was adapted from OpenStax Biology 36.4

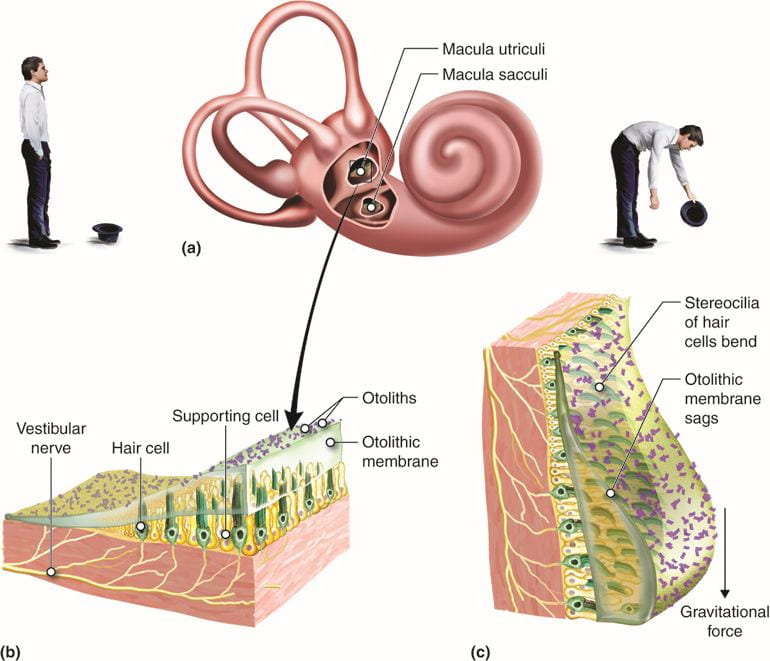

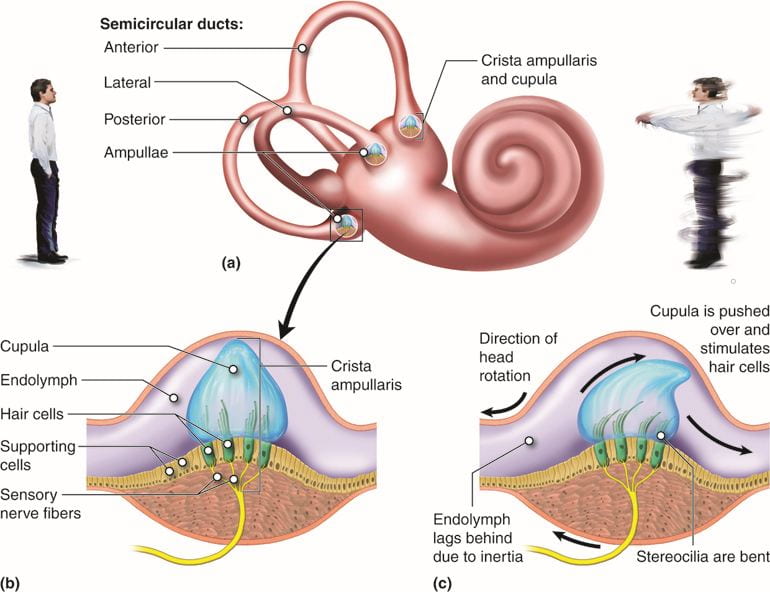

The vestibular system detects position and movement of our head in space; the stimuli associated with the vestibular system are linear acceleration (gravity) and angular acceleration and deceleration; mechanoreceptor cells in the vestibular system detect gravity based on head position, and changes in acceleration and deceleration in response to turning or tilting of the head.

The mammalian vestibular system and auditory system both use hair cells in the ear, but they are located in different places and activated in different ways. Auditory hair cells are located within the cochlea, and vestibular hair cells are located within the vestibular labyrinth which is adjacent to the cochlea.

Hair cells in the vestibular labyrinth detect stimuli in two ways:

- Some hair cells lie below a gelatinous layer, with their stereocilia projecting into the gelatin. Embedded in this gelatin are calcium carbonate crystals, like tiny rocks, that move in response to gravity. Any time the head is tilted at an angle or is subject to acceleration or deceleration, these crystals cause the gelatin to shift, bending the stereocilia. The bending of the stereocilia stimulates the neurons, and they signal to the brain that the head is tilted, allowing the maintenance of balance.

- Some hair cells project into a gelatinous cap called the cupula. When the head turns, the fluid in the canals shifts, thereby bending stereocilia and sending signals to the brain. When movement stops, the movement of the fluid within the canals slows or stops.

This video provides a quick overview of the mammalian vestibular system:

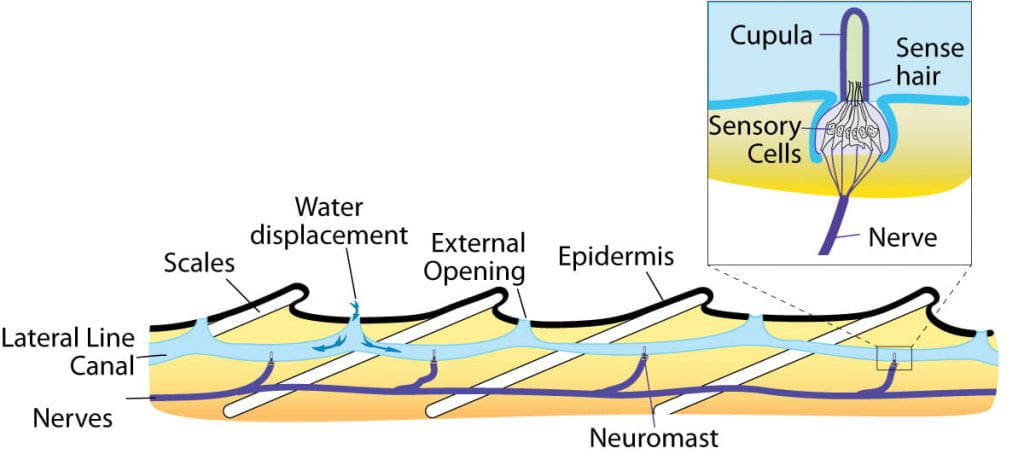

A similar system involving hair cells and a cupula is present at the lateral line of bony fish, which are used to detect changes in water pressure.

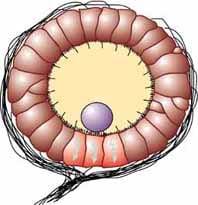

Many invertebrates detect balance through a structure called a statocyst, a ball-shaped organ lined with inward-facing hair cells and containing statoliths, dense particles similar to calcium carbonate crystals in the vertebrate vestibular labyrinth. Any movement causes the statoliths to change location inside the statocyst, activating different hair cells as they move.

This video provides an engaging review of mammalian hearing and balance (bonus points if you get the movie reference!)

Photoreceptors: Vision

The information below was adapted from OpenStax Biology 36.5

As with auditory stimuli, light travels in waves. The pressure waves that create sound must travel in a medium: a gas, a liquid, or a solid. In contrast, light is composed of electromagnetic waves and needs no medium; light can travel in a vacuum (this is why we can see stars from space.) The behavior of light can be discussed in terms of the behavior of waves and also in terms of the behavior of the fundamental unit of light: a packet of electromagnetic radiation called a photon. Humans can perceive just a small slice of the entire electromagnetic spectrum, which includes radiation that we cannot see as light because it is below the frequency of visible red light and above the frequency of visible violet light, which are the limits of vertebrate light detection.

Certain variables are important when discussing perception of light:

- Wavelength (which varies inversely with frequency) is detected as hue, or color. Light at the red end of the visible spectrum has longer wavelengths (and is lower frequency), while light at the violet end has shorter wavelengths (and is higher frequency). The wavelength of light is expressed in nanometers (nm); one nanometer is one billionth of a meter. Humans perceive light that ranges between approximately 380 nm and 740 nm. Some other animals, though, can detect wavelengths outside of the human range. For example, bees see near-ultraviolet light in order to locate nectar guides on flowers, and some non-avian reptiles sense infrared light (heat that prey gives off).

- Wave amplitude is perceived as luminous intensity, or brightness.

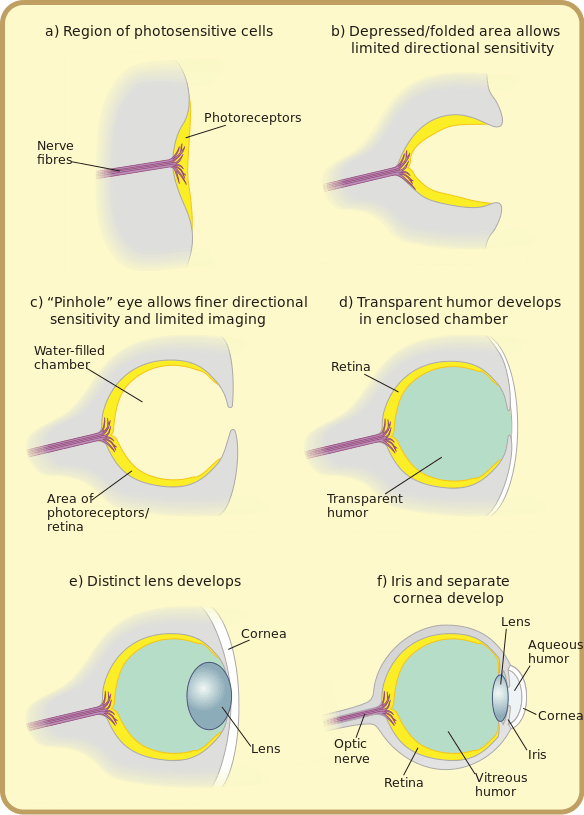

Detection of light occurs through photoreceptors, cells that contain pigment-absorbing molecules that absorb light. Photoreceptor cells are typically located in light-collecting organs called eyes. Eyes vary in structure in different types of animals and include:

- eye cups in flatworms, which are dimple-shaped structures that detect the direction of a light source

- compound eyes of arthropods, which contain multiple lenses and detect shapes, patterns, and movements

- pinhole eyes in the nautilus, which contain no lens and forms simple, low-resolution images

- simple eyes of cephalopods and vertebrates, which contain a single lens and form high-resolution images

Many of these types of eyes, which are present in living organisms today, may have also represented a pathway of evolution from a simple patch of photosensitive cells to simple lens eyes of vertebrates and cephalopods:

The image below illustrates several (though not all!) different types of eyes present in different groups of animals, and also shows an example of what an image might look like as perceived by animals with that type of eye

The video below compares and contrasts different types of eyes:

This video describes the evolutionary origins of the human eye:

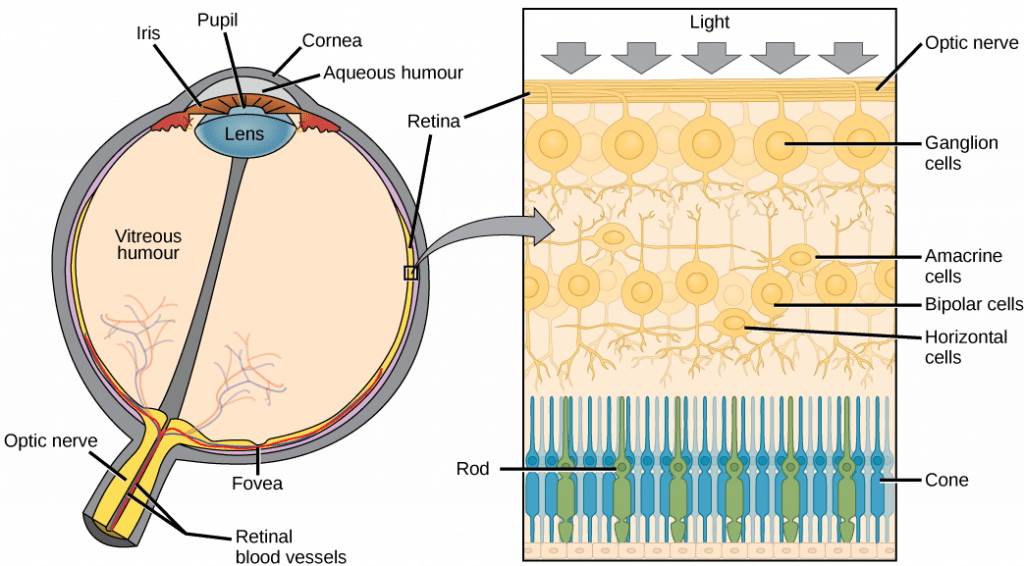

The vertebrate eye contains (among other structures):

- Cornea: transparent sheet of connective tissue, functions with the lens to focus light on the retina

- Iris: pigmented ring of muscle that controls amount of light entering eye

- Pupil: hole in center of iris

- Lens: crystalline, curved structure that focuses light on the cornea (by bending, not by moving) in conjunction with the cornea

- Retina: thin layer of photoreceptor cells and neurons

- Photoreceptor cells: light-detecting sensory cells

- Fovea: site of retina with only cones, area of highest visual resolution

- Optic nerve: axons of the ganglion cells

The vertebrate eye is pretty good at forming high-resolution images, though perhaps we are a little biased in making that assessment. But it turns out that that the vertebrate eye is actually far from ideal. In fact, the cephalopod eye, which looks the same on the surface but evolved independently, is far better. Here is a comparison between the vertebrate and cephalopod eyes:

- Cephalopod eyes move the lens to focus (like in a camera), rather than changing lens shape as in the vertebrate eye; the result in vertebrates is age-related loss of resolution as the lens loses flexibility over time

- Vertebrate eyes have an “inverted” retina, where blood vessels and nerves are in front of the photoreceptor cells, unlike in the cephalopod eye where the nerves are behind the photoreceptor cells; the result in vertebrates is the blind spot as well age-related macular degeneration and increased likelihood of retina detachment (a severe medical emergency) due to the loose association between the retina and the back of the eye

Regardless of the structure of the eye, all photoreception relies on light-absorbing pigment molecules embedded in the photoreceptor cells. This pigment is called retinal, and it is contained in a protein called opsin . Together, they form a complex called rhodopsin, that allow us to detect light and color. Both the protein and the pigment are essential for this process:

- The pigment: retinal, reversibly changes shape when it is hit by a photon of light (this process is extremely similar to detection of red vs far-red light by phytochrome in plants.)

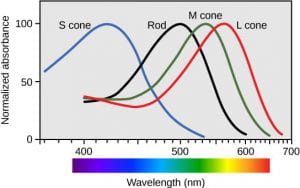

- The protein: opsin, holds the retinal pigment and changes shape/activity when the retinal changes shape in response to absorption of light. Opsins are responsible for our ability to perceive differences in color or hue. Humans have three color-sensitive opsins: S opsin (short-wavelength opsin), M opsin (medium-wavelength opsin), and L opsin (long-wavelength opsin).

- The photoreceptor cells: rods and cones each contain a unique opsin that causes the cell the cell to be most sensitive to a specific wavelength of light. Keep in mind that the retinal is always the same; it is the opsin that varies in different photoreceptor cells

- Cones (which are cone-shaped) each contain a single type of color-sensitive opsin, making each cone most sensitive to a particular hue or color of light. Though we only have three types of cones (due to the three types of color-sensitive opsins), we are able to detect so much variation in hue to do activation of different combinations of cones at the same time. Cones require high-levels of light to work, which is why we can’t perceive color well in the dark. Cones are heavily concentrated at the fovea and are useful for focusing on important visual details.

- Rods (which are rod-shaped) each contain a fourth type of opsin called rod opsin, which is activated by an intermediate wavelength of light; rods are not color-sensitive, but they are capable of working in low-levels of light. (This feature of rods is why we cannot perceive color well in dim light). Rods are heavily concentrated at the periphery (outer edges) of the retina, and are useful for detecting movement in our field of vision.

This video provides a brief explanation of how we can perceive so many different colors with only three types of cones:

What happens when a photon activates rhodopsin? Unlike all the other sensory systems we have discussed, a rod or cone cell hyperpolarizes when its rhodopsins are activated by light, and it depolarizes when its rhodopsins are in the dark. This means that, when in the dark, our rods and cones are depolarized and thus releasing neurotransmitters to their synapsed bipolar cells. When a rod or cone cell is activated by light, it hyperpolarizes and stops releasing neurotransmitter.

This video provides an engaging review of vertebrate eye function:

BONUS Information!

The information below is NOT required for the learning objectives of this course; we share it below if you are interested in learning more about other sensory systems in vertebrates.

Chemoreceptors: Taste (Gustation) and Smell (Olfaction)

The information below was adapted from OpenStax Biology 36.3

Taste, also called gustation, and smell, also called olfaction, are interconnected senses. Both involve molecules of the stimulus entering the body and bonding to receptors, relying on chemoreceptors, receptors that are sensitive to specific chemicals. Just as each photoreceptor cell is sensitive to a specific wavelength of light based on the opsin present in the cell, each chemoreceptor cell is sensitive to a particular molecule based on the protein receptor present in the cell.

Chemosensation is the evolutionarily oldest of all senses. The video below discusses chemosensation (and several “weird” sensory systems):

Chemoreceptors and Taste: the Gustatory System

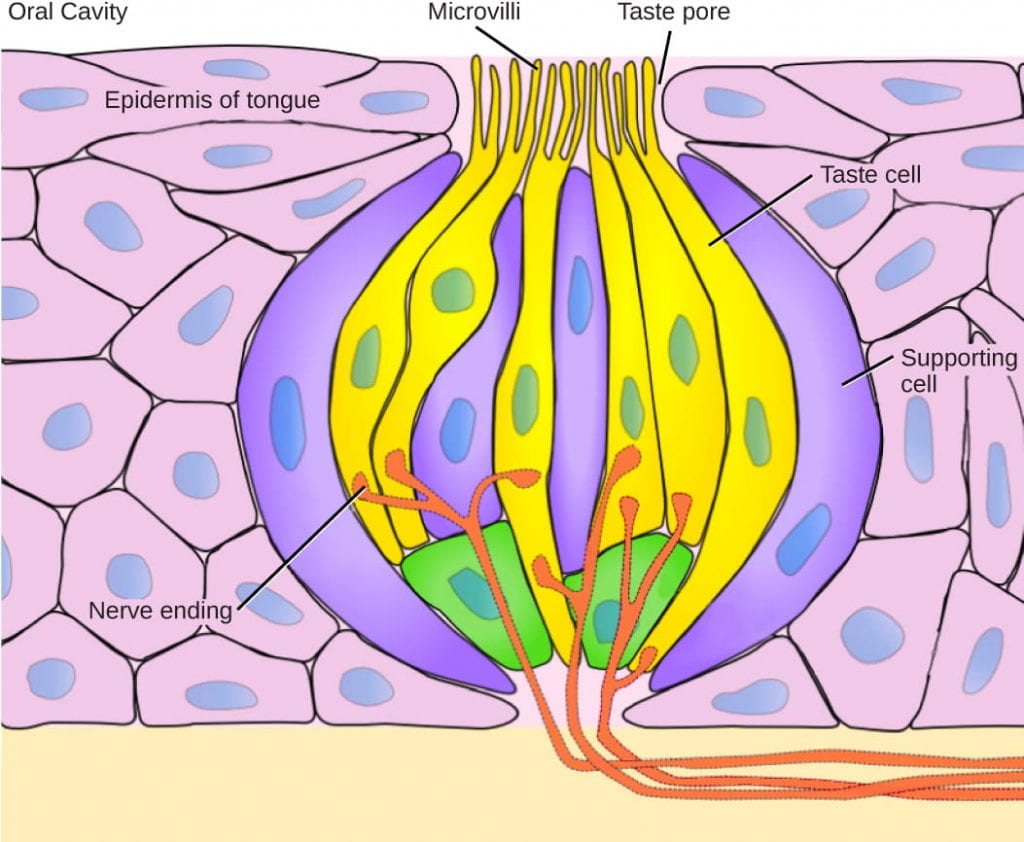

The primary tastes detected by humans are sweet, sour, bitter, salty and umami (savoriness, which tends to indicate that a food is high in protein).

Detecting a taste relies on activation of specific chemical receptors in taste receptor cells ( gustatory receptors). When the specific chemical (tastant) binds the receptor, the receptor cell becomes depolarized and releases neurotransmitter on its synapsed afferent neuron. As in other sensory systems, specificity in taste occurs because each taste receptor cell has only one type of protein receptor which is sensitive to either sweet, sour, bitter, salty, or umami. The process of depolarization differs based on the specific type of gustatory receptor:

- A salty tastant (containing NaCl) provides the sodium ions (Na+) that enter the taste receptor cells and excite them directly.

- Sour tastants are acids cause an increase hydrogen ion (H+) concentrations in the taste receptor cells, thus depolarizing them.

- Sweet, bitter, and umami tastants cause activation of an enzyme that causes opening of an ion channel, thus depolarizing the taste receptor cells.

- Spiciness isn’t detected by taste buds at all, but is actually due to activation of pain receptors (nociceptors)! (More on pain perception at the bottom of this page)

The primary organ of taste is the taste bud. A taste bud is a cluster of gustatory receptors (taste receptor cells) that are located within the bumps on the tongue called papillae (singular: papilla). Each taste bud contains all five types of gustatory receptors (the taste map is totally false), which are elongated cells with hair-like processes called microvilli at the tips that extend into the taste bud pore. Tastants must be dissolved in saliva to bind with and stimulate the receptors on the microvilli, which is why the sense of taste isn’t as strong when your mouth is dry.

Chemoreceptors and Smell: the Olfactory System

Flavor includes a lot more than just the five primary tastes; most people can detect a difference between the sweet flavors of different types of fruit rather than detecting all of them as just “sweet.” But the nuance of flavor doesn’t actually come from gustation at all; it comes from our sense of smell. This is why many people temporarily lose their sense of taste when they have a cold or other severe nasal congestion.

All odors that we perceive are molecules in the air we breathe. If a substance does not release molecules into the air from its surface, it has no smell. And if a human or other animal does not have a receptor that recognizes a specific molecule, then that molecule has no smell. Humans have about 350 olfactory receptor subtypes that work in various combinations to allow us to sense about 10,000 different odors. (As you may be expecting by now, each olfactory receptor cell has only one type of olfactory receptor protein, meaning each receptor cell is specific to only one type of odorant.) For comparison, mice have about 1,300 olfactory receptor types and therefore probably sense many more odors than do humans.

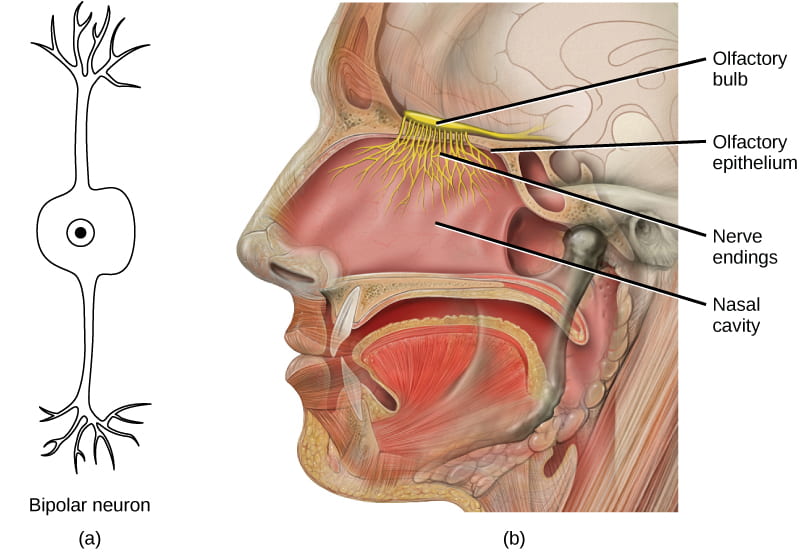

How does the sense of smell work?

- Odorants (odor molecules) enter the nose and dissolve in the olfactory epithelium, located at the back of the nasal cavity. The olfactory epithelium is a collection of specialized olfactory receptors in the back of the nasal cavity that spans an area about 5 cm2 in humans. Similar to tastants, which must be dissolved in saliva, an odorant molecule must be dissolved in mucus in order to be detected by its receptor.

- An olfactory receptor, which is a dendrite of a specialized sensory neuron, responds when it binds certain molecules inhaled from the environment by sending impulses directly to the olfactory bulb of the brain. Humans have about 12 million olfactory receptors, distributed among hundreds of different receptor types that respond to different odors. Twelve million seems like a large number of receptors, but compare that to other animals: rabbits have about 100 million, most dogs have about 1 billion, and bloodhounds, dogs selectively bred for their sense of smell, have about 4 billion. The overall size of the olfactory epithelium also differs between species, with that of bloodhounds, for example, being many times larger than that of humans.

- Each olfactory neuron has a single dendrite buried in the olfactory epithelium, and extending from this dendrite are hair-like cilia that trap odorant molecules. The sensory receptors on the cilia are proteins, and slight variations in the protein sequences make them sensitive to different odorants.

- Each olfactory sensory neuron has only one type of receptor protein on its cilia, and the receptors are specialized to detect specific odorants, so each olfactory neuron is capable of detecting only a single type of odorant molecule.

- When an odorant binds with a receptor that recognizes it, the sensory neuron associated with the receptor is is depolarized and relays action potentials to the brain.

- Olfactory stimulation is the only sensory information that directly reaches the cerebral cortex, whereas other sensations are relayed through the thalamus.

Our ability to detect and interpret flavor is due to the combination of gustatory and olfactory senses:

- Taste receptors are responsible for the sense of how salty, sweet, bitter, sour, or savory a food is, via tastants dissolved in saliva

- Olfactory receptors are responsible for the flavor of a food, via odorants detected in the olfactory epithelium during chewing, through a process called retronasal olfaction (the flow of air from the back of the throat up to the olfactory epithelium via the back of the nose)

This video review how olfaction works:

This video provides an engaging review of olfaction and gustation:

Nociceptors: Tissue Damage and Pain

Pain is the name given to nociception, which is the neural processing in response to tissue damage. Pain is caused by both true sources of injury, such as contact with a corrosive chemical, and also by harmless stimuli that mimic the action of damaging stimuli, such as contact with capsaicins, the compounds that cause peppers to taste hot (and which are used in self-defense pepper sprays and certain topical medications). Peppers taste “hot” because the protein receptors that bind capsaicin open the same calcium channels that are activated by heat-sensitive thermoreceptors.

There are many different types of nociceptors and we will not describe them in this course, but the important thing to understand is that different types of nociceptors are activated by different types of tissue damage, including extremes of hot or cold, toxic chemicals, and extreme mechanical deformation such as stretching, cuts, and tears.

Nociception starts at the sensory receptors, but pain does not actually start until it is communicated to the brain; pain is the interpretation of the tissue damage, not the actual stimulus itself. There are several nociceptive pathways to and through the brain, including through the thalamus (like most other sensory systems) and directly to the hypothalamus , which modulates the cardiovascular and neuroendocrine functions of the autonomic nervous system, where it can directly activate the fight-or-flight response.

This video discusses nociceptor function while explaining how pain relievers work (the details of how pain relievers work are not relevant to this course, though you may find the discussion interesting):

Here are some additional videos to help you put this all together (in a more entertaining way than many of the videos above). Note that these videos do not provide any new information, but they may help you better integrate all the information previously discussed: