Learning Objectives

- Distinguish between osmoregulators and osmoconformers, and give examples of each type of organism and their respective environments

- Explain the roles of active and passive movement of ions in osmoregulation

- Identify the classes of biomolecules that generate nitrogenous wastes, and explain the advantages and disadvantages of ammonia, urea, and uric acid for nitrogenous waste excretion

- Identify and describe patterns of osmoregulation and common principles of nitrogenous waste excretion in different animal lineages, including vertebrate and invertebrate examples

Water Balance in Animals: Osmoconformers vs Osmoregulators

The information below was adapted from OpenStax Biology 41.1 and OpenStax Biology 5.2

All living things require water to survive, including within individual cells and within tissues for multicellular organisms. Water is never moved directly (there is no “pump” to move water in an organism’s body). We have previously discussed how plants acquire and move water within their bodies by regulating water potential; here we will discuss how animals use concentrations of ions (aka electrolytes) and other solutes in their cells to regulate the movement of water into or out of their cells, tissues, and bodies.

Before we go in depth on animal strategies related to water balance, we will first briefly review the concept of osmosis. Osmosis is essentially the diffusion of water down its concentration gradient through a semipermeable membrane. Though we don’t usually think of water as having a concentration gradient, water’s concentration gradient is inversely proportional to the concentration of solutes in the water. Osmolarity describes the total solute concentration of a solution. Osmotic pressure is the pressure exerted on a membrane to equalize the solute concentration on either side of the membrane. Osmotic pressure is influenced by the concentration of solutes in a solution and is directly proportional to the number of solute atoms or molecules and not dependent on the size of the solute molecules.

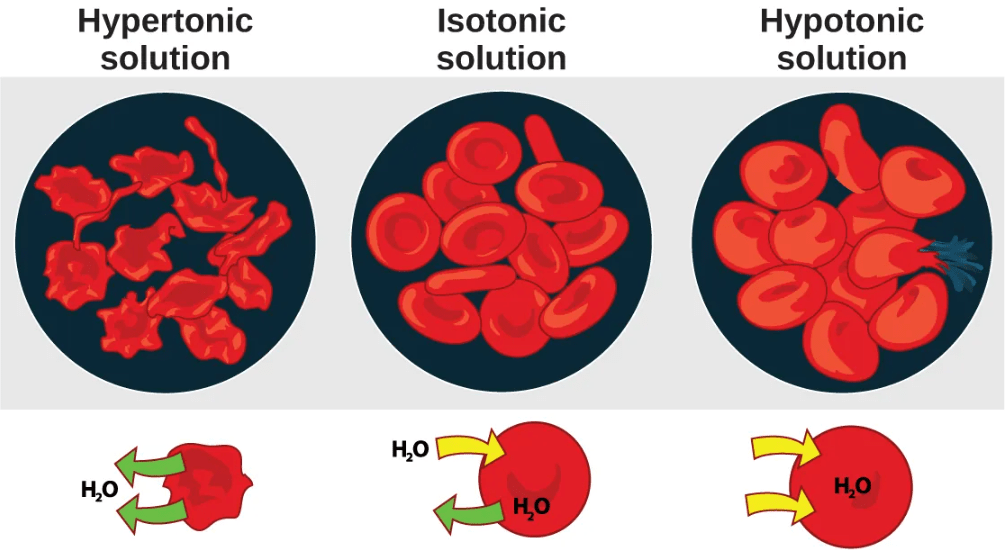

We can predict the movement of water from one side of a semipermeable membrane (such as the plasma membrane of a cell) to the other side by looking at the relative osmolarity on each side of the membrane:

- In a hypotonic situation, the extracellular fluid has lower osmolarity (lower concentration of solutes) than the cell cytoplasm, and water enters the cell as a result. (In living systems, the point of reference is always the cytoplasm, so the prefix hypo– means that the extracellular fluid has a lower concentration of solutes, or a lower osmolarity, than the cell cytoplasm.) It also means that the extracellular fluid has a higher concentration of water in the solution than does the cell. In this situation, water will follow its concentration gradient and enter the cell.

- In a hypertonic solution, the extracellular fluid has higher osmolarity (higher concentration of solutes) than the cell cytoplasm, and water exits the cell as a result. (The prefix hyper– refers to the extracellular fluid having a higher osmolarity than the cell’s cytoplasm.) It also means that the cell cytoplasm has a higher concentration of water than does the extracellular fluid. Because the cell has a relatively higher concentration of water, water will leave the cell.

- In an isotonic solution, the extracellular fluid has the same osmolarity (solute concentration) as the cell cytoplasm. If the osmolarity of the cell matches that of the extracellular fluid, there will be no net movement of water into or out of the cell, although water will still move in and out.

Animals have two major strategies related to water balance:

- osmoregulating: maintaining an internal cellular environment with specific salt and water concentration in their tissues that is independent of the external environment; as a result, the internal cellular environment could be either hypertonic or hypotonic to the external environment, depending on the specific external environment (e.g. salt water, fresh water, terrestrial systems, etc.).

Many vertebrates are osmoregulators, including most fish. About 90 percent of all bony fish are restricted to either freshwater or seawater, and they are incapable of osmotic regulation in the opposite environment.

- osmoconforming: maintaining a an internal cellular environment that is isotonic to the external environment, meaning that there no net movement of water into or out of the animal’s cells relative to the environment; however, although the internal cellular environment is isotonic to the environment, the specific ions and dissolved solutes inside of the cells are typically quite different from that of the external environment as necessary for cellular function. Even though osmoconformers are isotonic to the external environment, they can still have a relatively narrow range of salinity in which they can survive.

Most marine invertebrates are isotonic with sea water (osmoconformers). Their body fluid concentrations conform to changes in seawater concentration.

Cartilaginous fish such as sharks are also isotonic with sea water, but they do not have the same ion composition as the water; instead, they maintain osmotic balance by storing large concentrations of urea. So although they are osmoconforming with their saltwater environment, they actively excrete excess sodium and chloride ions from their blood.

Osmoregulation Requires Movement of Ions

The information below was adapted from OpenStax Biology 41.1

Water can pass through membranes by passive diffusion, but ions cannot. Organisms move ions in order to move water, which follows down its concentration gradient by osmosis. If ions could passively diffuse across membranes, osmoregulation would be largely impossible.

Movement of ions across a cell membrane can only be accomplished by either facilitated diffusion or active transport. Facilitated diffusion requires protein-based channels for moving the solute. Active transport requires energy in the form of ATP conversion, carrier proteins, or pumps in order to move ions against the concentration gradient.

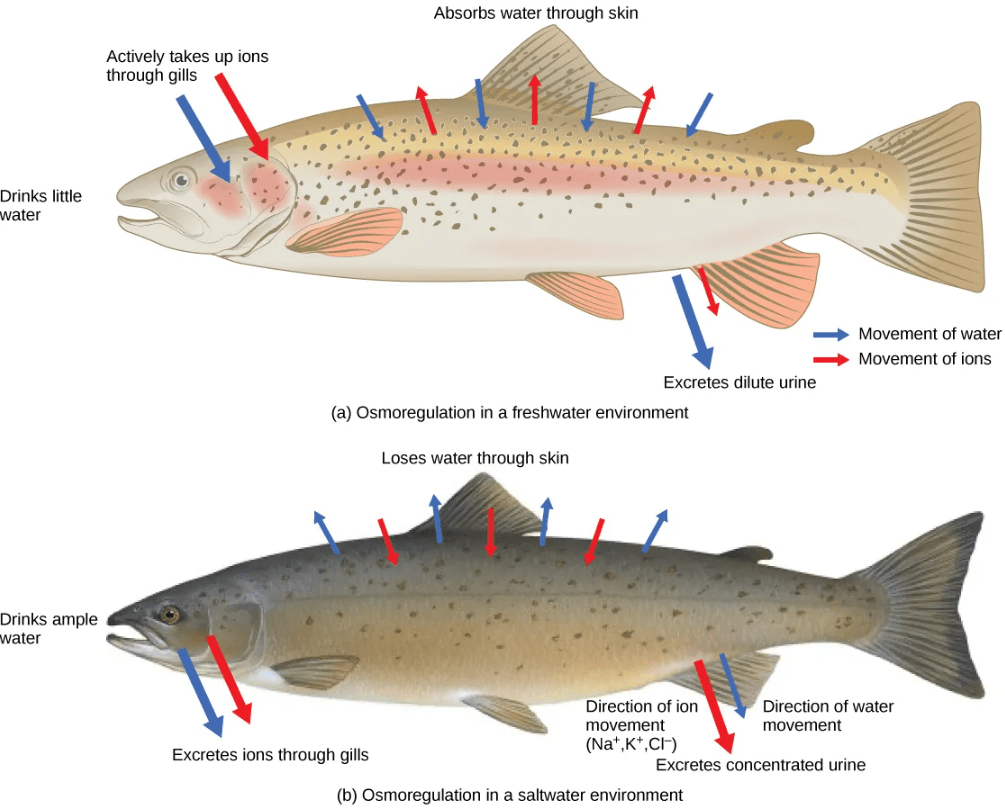

For example, freshwater fish constantly gain water and lose ions to the freshwater environment, and must actively transport ions back into their cells from the external environment. Saltwater fish constantly lose water and gain ions from the saltwater environment, and must actively pump ions out of their cells back into the external environment.

A few fishes like salmon spend part of their lives in freshwater, and part in sea water. When they live in fresh water, their bodies tend to take up water because the environment is relatively hypotonic. In such hypotonic environments, these fish do not drink much water. Instead, they pass a lot of very dilute urine, and they achieve electrolyte balance by active transport of salts through the gills. When they move to a hypertonic marine environment, these fish start drinking sea water; they excrete the excess salts through their gills and their urine.

This video gives an overview of osmoregulation in different types of fish:

Removal of Nitrogenous Wastes as Mechanisms of Osmoregulation

The information below was adapted from OpenStax Biology 41.4

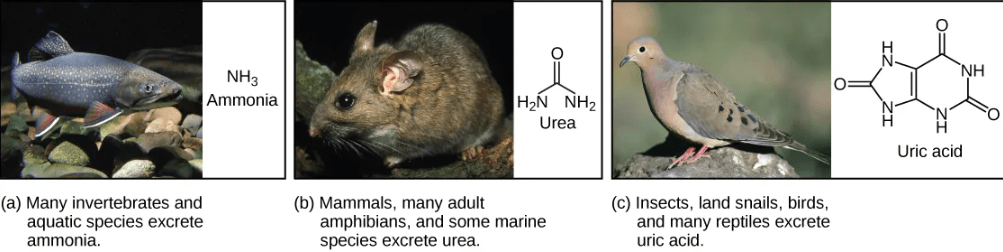

Of the four major macromolecules in biological systems, both proteins and nucleic acids contain nitrogen. When proteins and nucleic acids are broken down, the carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen are extracted and stored in the form of carbohydrates and fats. But excess nitrogen forms toxic ammonia and must be excreted from the body. Different mechanisms of nitrogenous waste excretion affect osmoregulation with varying tradeoffs:

- Ammonia: Fish and other animals that live in aquatic environment tend to excrete nitrogenous waste directly as ammonia. The formation of ammonia itself requires energy in the form of ATP and large quantities of water to dilute it out of a biological system.

- Urea: Terrestrial organisms with less access to the amount of water necessary to dilute ammonia have evolved other mechanisms to excrete nitrogenous wastes. Animals such as mammals detoxify ammonia by converting it to relatively nontoxic urea. Urea is made in the liver and excreted in urine. This process requires a higher ATP cost, but less loss of water.

- Uric acid: Birds, reptiles, and most terrestrial arthropods convert toxic ammonia to uric acid or the closely related compound guanine (guano) instead of urea. Uric acid is insoluble in water and tends to form a white paste or powder; thus it results in the least water loss of any mechanism for excreting nitrogenous waste. However, conversion of ammonia to uric acid requires more energy and is much more complex than conversion of ammonia to urea.

The video below describes the origins of nitrogenous wastes, the reason they are problematic, and provides an overview of some of the different mechanisms of removal of nitrogenous wastes in different lineages of organisms:

Patterns of Osmoregulation and Principles of Nitrogenous Waste Excretion

The information below was adapted from OpenStax Biology 41.3 and OpenStax Biology 41.2

All organisms must rid their cells of metabolic wastes, particularly toxic nitrogenous wastes. Nitrogenous waste removal is mediated by the excretory system. Excretory systems also frequently play roles in osmoregulation. Excretory systems in different lineages of animals include vacuoles, flame cells, Malpighian tubules, and kidneys:

- Contractile Vacuoles in Microorganisms: In some unicellular eukaryotic organisms, such as the amoeba, cellular wastes and excess water are excreted by exocytosis (effectively the opposite of endocytosis), when a structure called a contractile vacuole merges with the cell membrane to expel wastes into the environment. Contractile vacuoles (CV) should not be confused with vacuoles, which store food or water.

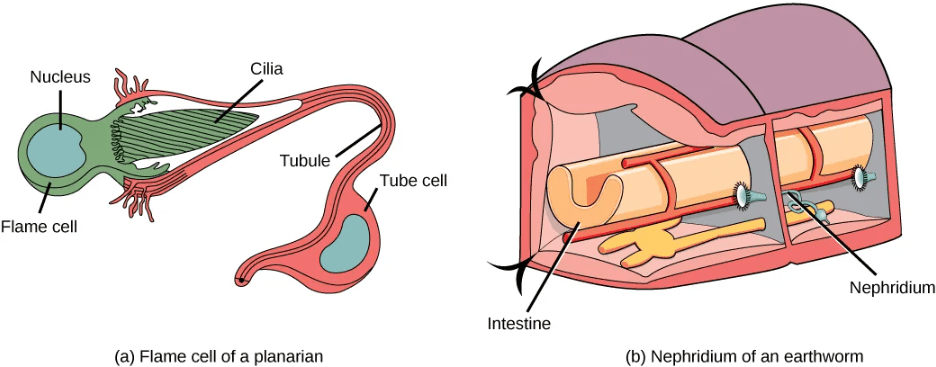

- Flame Cells in Planaria: Planaria are flatworms that live in fresh water. Their excretory system consists of two tubules connected to a highly branched duct system. The cells in the tubules are called flame cells (or protonephridia) because they have a cluster of cilia that looks like a flickering flame when viewed under the microscope. The cilia propel waste matter down the tubules and out of the body through excretory pores that open on the body surface; cilia also draw water from the interstitial fluid, allowing for filtration. Any valuable metabolites are recovered by reabsorption. They also maintain the organism’s osmotic balance.

- Nephridia in Annelids: The Earthworms (annelids) excretory system is composed of structures called nephridia. One pair of nephridia is present on each segment of the earthworm. They are similar to flame cells in that they have a tubule with cilia. Excretion occurs through a pore called the nephridiopore. Nephridia are different from flame cells in that they have a system for tubular reabsorption by a capillary network before excretion.

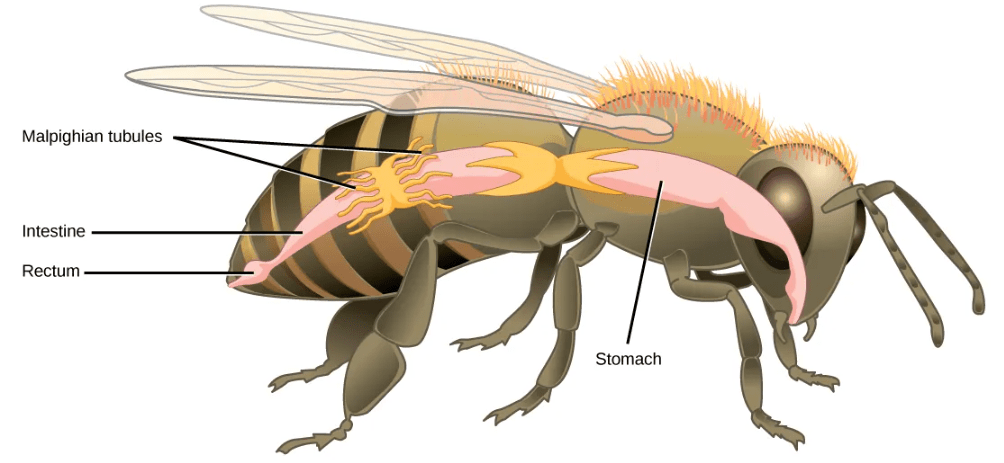

- Malpighian Tubules in Insects: Malpighian tubules are found lining the gut of some species of arthropods, such as the bee. They are usually found in pairs and the number of tubules varies with the species of insect. Malpighian tubules are convoluted, which increases their surface area, and they are lined with microvilli for reabsorption and maintenance of osmotic balance. Malpighian tubules work cooperatively with specialized glands in the wall of the rectum. Body fluids are not filtered as in the case of nephridia; urine is produced by tubular secretion mechanisms by the cells lining the Malpighian tubules that are bathed in hemolymph (a mixture of blood and interstitial fluid that is found in insects and other arthropods as well as most mollusks). Metabolic wastes like uric acid freely diffuse into the tubules. There are exchange pumps lining the tubules, which actively transport H+ ions into the cell and K+ or Na+ ions out; water passively follows to form urine. The secretion of ions alters the osmotic pressure which draws water, electrolytes, and nitrogenous waste (uric acid) into the tubules. Water and electrolytes are reabsorbed when these organisms are faced with low-water environments, and uric acid is excreted as a thick paste or powder. Not dissolving wastes in water helps these organisms to conserve water, which is especially important for life in dry environments.

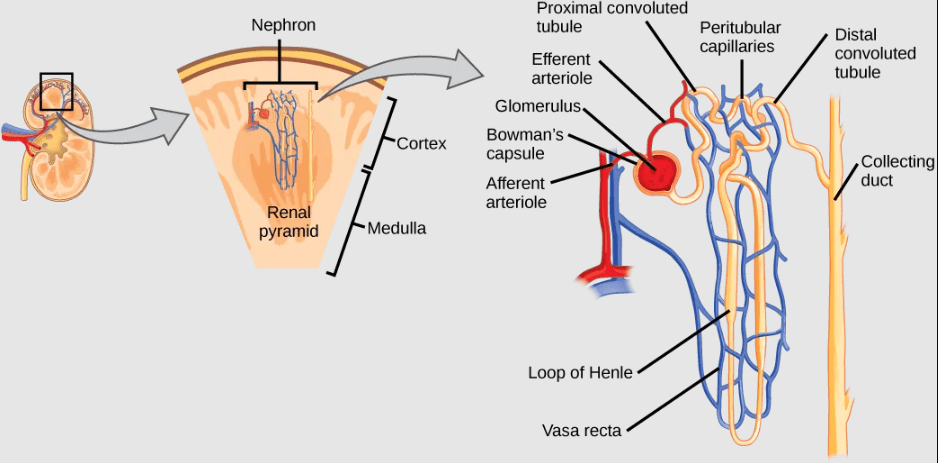

- Kidneys and Nephrons in Mammals: Mammalian kidneys are bean-shaped organs containing convoluted structures called nephrons that produce urine by filtering all the blood in the body multiple times per day. Pre-urine filtrate from the blood enters the nephron, then ions, nutrients, and water is reabsorbed back into the blood as the filtrate passes through the nephron. Active transport of ions from the nephron is required to drive diffusion of water and other solutes out of the filtrate. Waste becomes concentrated in the urine, which is then stored in the bladder prior to excretion.